A Leading Edge Camera for Molecules, Max Planck researchers in Heidelberger film fast molecular motion for the first time.

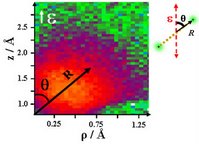

| Fig.1: One of the many snapshots that the physicists took of the heavy hydrogen molecule. Each dot in the image represents a specific angle between laser polarisation and the molecular axis |

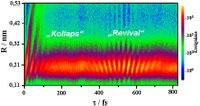

| Fig. 2: Development of the wave packet over a period of time. The distance between the deuterium nuclei (R) is plotted against the time. |

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg have visualised vibration and rotation in the nuclei of a hydrogen molecule as a quantum mechanical wave packet. What is more, this has been achieved on an extremely short spatio-temporal scale. They "photographed" the molecule using intensive, ultrashort laser pulses at different points in time and compiled a film from the separate images. This allowed them to visualise the quantum mechanical wave pattern of the vibrating and rotating molecule (Physical Review Letters, Online-Edition, November 6, 2006).

Cameras and light microscopes are not viable options when photographing molecules: a hydrogen molecule is around 5,000 times smaller than the wavelength of visible light and it is therefore not possible to create an optical image of these molecules. Instead, for some time Max Planck researchers have been using pump-probe technology to make high-resolution and ultrahigh-speed images. The molecules are first "bumped" with a "pump" laser pulse and then after a specific time measured with a "probe" laser pulse.

The scientists are particularly interested in the smallest and fastest molecule, the hydrogen molecule. In order to create an image of the ultrafast molecular motion, laser pulses in the past have lasted too long. The two nuclei in the hydrogen molecule vibrate backwards and forwards so quickly that even visible light only vibrates five times in the same time. However, as in photography, creating a sharp image of fast events requires extremely short exposure time.

To shorten the "exposure time", researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics developed pump-probe apparatus with an average laser pulse duration of only six to seven femtoseconds, allowing molecular motion to be measured continuously for the first time. By comparison, light, which can orbit the earth around eight times in one second, only travels around two thousandths of a millimetre in seven femtoseconds. The scientists had to overcome tremendous technical challenges in accomplishing this. They kept the interval between the laser pulses stable to within 0.3 femtoseconds. Light only travels 100 nanometres in this time. For this reason, the optical components of the experiment were not allowed to move more than 500 atom diameters in relation to each other while the measurement was being taken.

For the measurement, the researchers used deuterium molecules, a compound of two heavy hydrogen atoms. They are not energetically excited, and are therefore in the quantum mechanical ground state. The first pump laser pulse removes an electron from a deuterium molecule and it is ionised. Adjusting to the new situation, the two nuclei of the ionised deuterium molecule move further apart and vibrate around a new resting position. The pump pulse also makes the molecule rotate. With the subsequent probe laser pulse the scientists remove the second electron from the molecule; as there are now no more electrons available for fusion and the positively charged nuclei repel each other, the remains of the molecule "explode"; the closer the two nuclei are to each other when the second ionisation takes place, the more violent the explosion. Using a "reaction microscope" which they developed some time ago, the researchers measure the energy of the two deuterium nuclei from which they calculate the distance between them and their positions at the moment of explosion. Altering the interval between the pump pulse and the subsequent probe pulse allows a snapshot of the movement of the nucleus at different times to be made (see fig. 1). A sequence of the separate images produces a "molecular film", giving an insight into the molecular dynamic.

In quantum mechanical terms, the vibrating deuterium nuclei are equivalent to a wave packet which starts off as a compact system and after a certain time breaks up - physicists call this "delocalising"; it is similar to the way a crowd of differently paced runners initially clumps together at the start of the track and after a while string out. This break up can be seen in Fig. 2. At the beginning, the movement measured in the wave packet (and thus in the nuclei) is still well localised, i.e. the pack of runners is still relatively dense and compact. After approximately 100 femtoseconds, the structure becomes "fuzzy" or delocalised: the runners are strung out along the whole of the track. The physicists were able to create an image in space and time of this "wave packet collapse". Furthermore, they also recorded how the wave packet regrouped after approximately 400 femtoseconds - there was a "revival". Using the image of the long-distance race, this means that the runners group together again in a dense crowd after a certain period.

With their extremely fast molecule camera, the researchers in Heidelberg have for the first time created a complete image of the dynamic of one of the fastest molecular systems over a previously unachieved short time scale. In future, by modelling the pump laser pulse, the wave packet will be created so that certain quantum mechanical processes take place in preference to others. The scientists want to manipulate and control the chemical reactions of larger molecules in this way. Experiments of this kind are already being carried out on methane molecules in the laboratory in Heidelberg.

Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science Press and Public Relations Department. [1] VIDEO IN AVI FORMAT, Visualisation of the quantum mechanical wave patterns of a vibrating and spinning molecule

Hofgartenstrasse 8, D-80539 Munich, PO Box 10 10 62, D-80084 Munich, Phone: +49-89-2108-1276, Fax: +49-89-2108-1207

E-mail: presse@gv.mpg.de Internet: http://www.mpg.de/, Responsibility for content: Dr. Bernd Wirsing (-1276)

Executive Editor: Dr. Andreas Trepte (-1238), Online-Editor: Michael Frewin (-1273), ISSN 0170-4656.

Original work: Th. Ergler, A. Rudenko, B. Feuerstein et al. Spatio-Temporal Imaging of Ultrafast Molecular Motion: ‘Collapse’ and Revival of D2+ Nuclear Wave Packet, Physical Review Letters, Vol. 97, No. 19, November 6, 2006 IN PDF FORMAT (166 KB)

Contact: Dr. Thorsten Ergler Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, HeidelbergTel.: +49 6221 516-452Fax: +49 06221 516-604E-mail: thorsten.ergler@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Technorati Tags: nanofibers or Nanoscientists and Nano or Nanotechnology and nanoparticles or Nanotech and nanotubes or nanochemistry and nanoscale or nanowires and Nanocantilevers or nanometrology and nanostructure or Nuclear Physics and quantum mechanical wave or femtoseconds

No comments:

Post a Comment