“Researchers have always measured the pulse immediately as it exited the laser, so they didn’t realize the extent to which the pulse became distorted by the time it reached the focus after traveling through the optics and lenses in the system,” said Rick Trebino, a professor in the Georgia Institute of Technology’s School of Physics and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Ultrafast Optical Physics.

“A lot of chemists and biologists use ultrafast lasers, so it was important that our device be easy to use because non-laser scientists don’t want to spend all day measuring their laser pulses,” noted Bowlan.

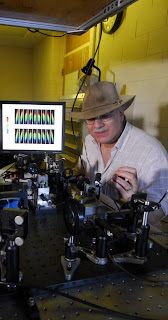

The research team – which also included former graduate students Pablo Gabolde and Selcuk Akturk – used the concept of interferometry to measure a pulse in space and time. Two pulses, one reference and one unknown, were sent through optical fibers. The fibers were mounted on a scanning stage so that the pulses could be measured at many locations around the focus.

The pulses were crossed and an interference pattern was recorded for each color of the pulse at each location with a digital camera. The patterns were used to determine the shape of the unknown pulse in space and time and to create movies showing how the intensity and color of the pulse changed in space and time as it focused.

“Because the laser pulses enter SEA TADPOLE through optical fibers, which only collect a very small portion of the light, the device naturally measures pulses with high spatial resolution and can measure them at a focus spot size smaller than a micron,” explained Bowlan. To further improve the spatial resolution of the device, the research team began to use specialized fibers, called near-field scanning optical microscopy fibers, which can resolve features smaller than the wavelength of the light.

The researchers tested the device by measuring ultrashort pulses focused by various lenses, since each lens can cause different complex distortions. To validate the measurements, Bowlan performed simulations of pulses propagating through the experimental lenses. Results showed that a common plano-convex lens displayed chromatic and spherical aberrations, whereas more expensive aspheric and doublet lenses exhibited mostly chromatic aberrations.

Spherical aberrations occur when the light that strikes the edges of the lens gets focused to a different point than the light that strikes the center, creating a larger, inhomogeneous focused spot size. Chromatic aberrations occur because the many colors in the laser travel at different speeds and do not stay together in space and time as the pulse passes through glass components in the experimental setup, such as lenses. As a result, each color arrives at the focus at a different time, creating a rainbow of colors in the electric field images.

Aberrations can drastically increase the pulse length, which decreases the laser intensity. A lower intensity forces researchers to increase the power of the laser, increasing the possibility of damaging the sample. Aberrations can also yield odd pulse and beam shapes at the focus, which complicate the interpretation of the experiment or application.

“Our system tells researchers what types of aberrations are present in instrumentation, which then allows them to test different lenses in the instrumentation setup or use a pulse shaper to create the desired pulse at the focus that’s free of distortions,” added Bowlan. ###

Contact: Abby Vogel avogel@gatech.edu 404-385-3364 Georgia Institute of Technology Research News

No comments:

Post a Comment